The New York Times

Role: Illustrator

On the day that Steve Jobs resigned as CEO of Apple, I was asked to illustrate an article for The New York Times that would mark the momentous occasion. In the article written by Steven Heller, notable designers, critics and editors offered their thoughts on Steve Jobs’ legacy and his most significant contributions to design. Contributors to this article included such design luminaries as Pentagram Design partner Paula Scher, writer and critic Phil Patton, Vignelli Design founder Massimo Vignelli, AIGA Director Ric Grefe, Unit Editions publisher Adrian Shaughnessy, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum design curator Ellen Lupton, Sterling Brands President Debbie Millman, Musician and Author Paul D. Miller, Metropolis Magazine Editor Martin Pedersen and the Chair of MFA Design Criticism at The School of Visual Arts, Alice Twemlow.

For the illustration, I wanted to draw on Steve Jobs and Apple’s historic past, but also tried to incorporate a contemporary visual style. The background of segmented spectrum colours coupled with the now legendary Rob Janoff rainbow scheme logo, helped form a striking image for the article’s illustration. The omnipresent symbol created by Janoff in 1977, was used from April of that year until August 1999. Janoff’s original apple logo design contained a rainbow, a nod towards Apple II, which was the world’s first computer to include a colour display. The logo itself debuted a little before the computer’s public launch. Janoff has said that there was no rhyme or reason behind the placement of the colours themselves, noting that Steve Jobs wanted to have green at the top “because that’s where the leaf was”. According to Janoff, the bite in the Apple logo was originally implemented so that people would know that it represented an apple, and not a cherry tomato. It also lent itself to a play on the word “byte”, a fitting reference for a technology company during that era. The Apple design with multi-coloured stripes was promptly approved for production by Steve Jobs. The artwork was then developed for print advertisements, signage hardware emblems and software labels on cassette tapes, all in preparation for the launch of the Apple II Computer in April of 1977 at the West Coast Computer Faire in San Francisco. For the next two decades, the now-famous rainbow version of the logo adorned all Apple products from its computer hardware, software packages and peripheries. The multi-coloured Apple logo had been in use for 22 years before it was finally discontinued by Steve Jobs less than a year after his return to Apple in 1997. In its place was a new logo that removed the colourful stripes and replaced them with a more modern monochromatic look that has taken on a variety of sizes and colours over the past few years. The overall shape of the logo, however, remains unchanged from its original inception more than 40 years ago.

The New York Times is an American newspaper based in New York City with worldwide influence and readership. Nicknamed the Gray Lady, the Times has long been regarded within the industry as the national newspaper of record. The paper's motto, All the News That's Fit to Print, appears in the upper left-hand corner of the front page. Founded in 1851, the paper has won more than 130 Pulitzer Prizes, more than any other newspaper; as well as being ranked top 18th in the world by circulation and 3rd in the United States. Today, the company headquarters are located in The New York Times Building on 620 Eighth Avenue. The paper is owned by The New York Times Company, which is publicly traded and is controlled by the Sulzberger family.

Link to article is here.

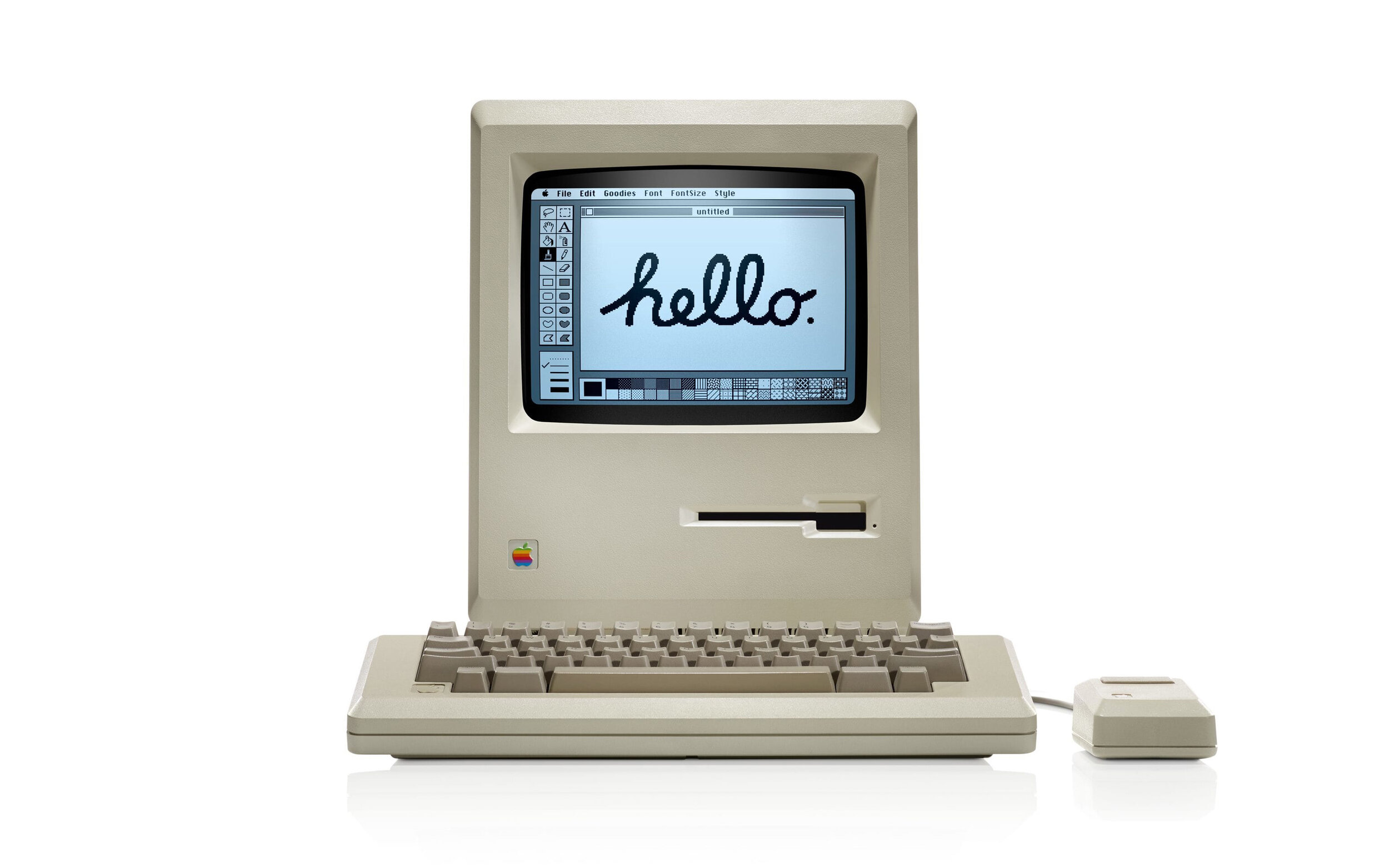

When the Macintosh was introduced, Steve Jobs became something of a pariah in the graphic design world. Apple ran a TV commercial that introduced the world to graphic designers, and in the next breath said that, because of the Macintosh, they were obsolete. Designers were so miffed, as I recall, that they denied Apple a design leadership award by the Art Directors Club for a few years thereafter. Like elephants, graphic designers’ trunks are filled with memories. But Jobs redeemed himself.

Not only did his products become integral to the graphic design community, but Apple essentially created new professions for designers. Of course, that was the inevitable double-edged sword. The Mac was so versatile as a production tool that it put traditional vendors — typesetters, color correctors, even some printers — out of business, and transferred those jobs to designers. But in short order, the Mac also increased the need for truly skilled and talented designers to offset “template” design.

Jobs was seriously design savvy, and proffered not just good but spectacular work. Now that he has resigned as C.E.O. (to be chairman of the board), some reflection is appropriate regarding his impact on graphic design. I asked notable designers, critics and editors to offer thoughts on Jobs’s lasting legacy, his most significant contributions to design and the possible consequences of his departure.

Paula Scher, Partner, Pentagram Design

Jobs created a company that was totally design driven, was branded as design driven and proved that by paying attention to human intuition and beauty of form instead of quarterly reports and “scientific” focus tests, he could create products that would become objects of desire all over the world.

I think the loss will be gradual and incremental. Jonathan Ive is still there. Their designers are still top-notch. They will maintain the culture. But the best design is the give and take between great designers and C.E.O.’s with true vision. True vision is irreplaceable and Jobs had it.

Phil Patton, Writer & Critic

Jobs believed design and technology could improve the world. “I want to put a ding in the universe,” he told me when I first met him in 1981. This was a sentence he often used. He scolded the nonbelievers.

He hired lots of designers, like Paul Rand and Frog Design, way before the current Apple crop and admired I.B.M. and Porsche design. The Jobs model will be cited as case study. The danger is that it will be seen as the only one — companies without a single strong C.E.O. can and must also have good design.

Massimo Vignelli, Vignelli Design

Steve Jobs never asked people what they wanted; he gave them what they needed. He had vision, courage and determination — to me, the most important attributes in life. His work will forever remain a beacon to enlightened industrialists.

Adrian Shaughnessy, Publisher, Unit Editions

He made computing sexy. In a world of Dells and Microsofts, Apple products were always designed for use by real people. For years I had to bite my tongue while I.T. geeks dissed Apple. If Jobs did nothing else, he dispelled the sneers.

Apple’s (and therefore Jobs’s) greatest contribution to design has been the elegance and simplicity of the tools they provide designers with. What I like best about Apple products (I’ve been buying them since the early ’90s) is the constant sense of improvement and refinement: a tireless search for simplicity and purity.

Ellen Lupton, Design Curator, Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum

Under Jobs’s leadership, Apple has created a unique product culture in which the physical object and the electronic interface come together as one. No other company has come close to doing it the way Apple has.

The iPod was certainly a watershed moment, because it brought Apple’s aesthetic and functional ideal to a new product category and a new market. It allowed people who will never be Apple computer users to engage with Apple products. The iPod instantly created (and dominated) a new type of product that changed culture in a big way. That doesn’t happen much.

Debbie Millman, President, Sterling Brands

Jobs is the ultimate corporate risk taker — he revolutionized the computer business, and the entire entertainment business.

Beyond aesthetics and functionality, I think Steve’s most significant contribution to design was his deep belief in knowing what people wanted. He was so sure of this, he never, ever conducted market research. This takes enormous belief in your vision and courage in your convictions.

Apple may survive, but how can anyone imagine that it could ever be a better organization without him? This isn’t replacing Shelley Long on “Cheers.”

Ric Grefé, Director, AIGA

Steve Jobs trusted intuition, but it was not just his instincts that were remarkable. He focused on his sense of what the emotional experience of real people would be in using technology — what people would love to do with technology, not what they would need. Form needn’t follow function; the two are intertwined, and don’t forget delight.

Paul D. Miller, Author, aka D.J. Spooky

In this era of hyper-unequal pay for executives, Steve Jobs is still, weirdly enough, a folk hero. He will be remembered as the anti-Big Brother, independent face of computing. Kind of like if Tesla had beat Edison.

By streamlining and having a relentless focus on ease of use, elegance and a firm control on the lines of production, Jobs absorbed the lesson of so many successful models: less is always slightly more. Closed models of production don’t work in this era — look at the rise of Google Android. But like 1950s America’s fascination with cars with tail fins, some things are just kind of cool, and classic.

Martin Pedersen, Editor, Metropolis Magazine

I was just thinking today that the most influential designer today isn’t Frank Gehry or Rem Koolhaas or Zaha Hadid, but Jonanthan Ive, Jobs’s head designer and, to some extent, his right-hand man. And Jobs, of course, oversees a whole host of products that have totally upended the industries they invaded: iMac (personal computers); iPod (the music industry); iPhone (pretty much everything); and now the iPad (media). Those were all immensely successful design efforts, overseen, art directed, if you will, by Jobs.

Jobs helped make design part of mainstream consciousness. He may be responsible for this more than any designer. Jobs famously ruled by instinct, and Apple won’t have that instinct in the future.

Alice Twemlow, Chair, MFA Design Criticism, School of Visual Arts, New York City

Leaving his irreversible impact on business aside, I’m interested in his influence on our social behavior. Obviously he changed the way people engage with music, information, news and entertainment, but his legacy also changes the way people engage (or don’t) with one another in public spaces: people are “talking” via NFC tags to advertisements and store windows as much as they are to one another; the texture and rhythm of our working day now has no definitive endpoint; and so on. There is a new imperative to look busy in public, to be texting, talking to someone on the phone and to be checking e-mail (preferably all at the same time). In cafes, once locations for talking, flirting, daydreaming, you now find ranks of freelancers, connected to their laptops by the umbilical cords of their earphones, eyes down. Jobs contributed to a complete reconfiguration of our social architecture.

His contribution to design’s canon of wonders, of course, is Jonathan Ive’s seductively slick, ice-cubes-of-the-gods product styling of eminently caressable handhelds and monitors that catapulted technology from the grubby engineer’s workshop into the millennial zeitgeist of the round-cornered, gloss-surfaced Wallpaper lifestyle. Jobs’s more significant contribution is in this remarkable set of tools he has provided designers with. It’s arguable that design has got better since the advent of the Apple Mac, but it’s certainly become more complex and awe-inspiring.

© 2025 The New York Times Company